Orangutan Natural History and Socioecology

Tags:

Natural History SocioecologyOrangutan Distribution

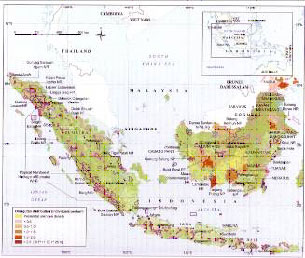

Orangutans are the only great ape outside of Africa and they are uniquely adapted to the tropical forests of Southeast Asia. During the Pleistocene, orangutans ranged throughout forests in Java, Sumatra, Borneo, Vietnam and southern China. As climate slowly changed over nearly 1.8 million years, the orangutan range shifted southward.

Orangutan populations have declined dramatically, perhaps by as much as 97%, in the 20th century (1) due to hunting and forest loss. Today orangutans are patchily distributed in fragmented lowland forests in Borneo and Sumatra. Tanjung Puting contains one of the largest and most concentrated populations of wild orangutans in the world.

Current Population Estimates

The most recent population estimate for Pongo abelii is around 7,300 individuals (2). For Bornean orangutans, numbers are between 45,000 and 69,000 individuals (3). With substantial habitat losses since 2003, when these estimates were obtained, it is likely that Bornean orangutan populations are substantially lower (4). Galdikas estimates there are less than 40,000 Bornean orangutans in the wild.

Two Species

Currently two orangutan species are recognized: Pongo abelii representing the Sumatran lineage and Pongo pygmaeus representing the Bornean lineage. Dividing the orangutan into two species was much debated in the 1990s, but this separation of species is supported by genetic analysis and a general attitude of “taxonomic inflation” in primatology. Recently, researchers have found that these two orangutan lineages differ more than the chimpanzee and the bonobo (5).

Pongo abelii and Pongo pygmaeus have been geographically isolated for at least 10,000 years by the Java Sea and large rivers on the Sunda shelf. But genetic analysis suggests that the species diverged long before this, when large distances effectively separated Bornean and Sumatran populations.

The appearance of the Bornean and Sumatran orangutan can be quite different. Bornean orangutans tend to have dark red or orange hair compared to the lighter colored Sumatran orangutans whose hair tends towards blonde, yellow, or a lighter shade of orange. Bornean orangutans rarely display the fine, dense facial hair characteristic of their bearded Sumatran cousins. Males differ more markedly than females, with many Bornean adult males having cheek pads that curve forward rather than lie flat on the face, and larger throat pouches compared to Sumatran orangutans.

Behaviorally, the Bornean and Sumatran orangutans show some differences, probably due to the ecological differences in their forest homes. Bornean forests are relatively fruit-poor. Since orangutans depend on large supplies of sugary, pulpy, ripe fruit, adult Bornean orangutans seem to spend more time living a semi-solitary lifestyle compared to Sumatran orangutans. This may account for the observation that tool use seems less prevalent among wild Bornean orangutans compared to their more social Sumatran cousins.

Despite some differences in morphology and behavior between Pongo abelii and Pongo pygmaeus, all orangutans share similar life histories and respond to the same major ecological and anthropogenic factors. Therefore, research conducted on both species helps scientists and conservation managers understand the “orangutan”.

Life History

Like other apes, orangutans have a slow life history which makes it difficult for them to recover from severe population losses (6). The average age of first breeding for females is around 15 years with a maximum reproductive age of 45 to 50 years (7). Unique to orangutans, females care for dependent offspring for at least six years (8), and have an interbirth interval of eight years (9), the longest of any mammal. The ecological cost of associating with multiple offspring best explains the long interbirth period (6).

Males and Females

Orangutans are large-bodied and exhibit extreme sexual dimorphism. Subadult males are about the size of adult females. At maturity, females may weigh about 40kg. At sexual maturity, males are about twice this size, weighing more than 80kg. Some wild males may actually weigh over 120 kg while in captivity males have weighed over 200 kg. Adult males also express secondary sexual characteristics including wide cheek pads and a well-developed throat sac which enables them to make periodic vocalizations known as long calls (10,8).

A Life in the Trees

Despite their large body size, orangutans are almost exclusively canopy-dwelling. Orangutans travel through the canopy where they find most of their food (fruit, young leaves, and bark). Females are more exclusively arboreal than males and Galdikas (8) has suggested several hypotheses. There is a higher energetic cost associated with carrying infants, so females may tend to stay in the canopy rather than spend energy climbing down and back up into the trees. Infants and juveniles may also be in greater danger on the ground, where pigs can attack them. In contrast, males, which travel alone are free to exploit more resources on the ground. This may explain why males are often observed feeding on termite nests, a food which females eat much less frequently – except when pregnant. Then they tend to forage on termites in the canopy.

Social Behavior

Orangutans are semi-solitary since fruit is not abundant enough to allow orangutans to be permanently gregarious. However, they do form parties to gain social benefits when there is an abundance of fruit (6).

Some observers, e.g. Galdikas (8) have noted a degree of sociality among adult Bornean females at Tanjung Puting. In addition, most observers, such as Galdikas (11), have documented that independent immature orangutans, particularly adolescent females, are almost gregarious and social compared to adult individuals of their species.

Adult females are often accompanied by their offspring, and even after reaching maturity, young adult females are known to establish home ranges near or overlapping with their mothers (8). This dispersal pattern may be considered a variation of female philopatry (6).

In contrast, males tend to disappear from the area where they were born as they mature and observations of wild orangutans suggest males are more likely to disperse long-distances (12).

Females, juveniles and subadult males may encounter and tolerate one another when temporarily congregating in a location with abundant fruit. In contrast, adult males do not tolerate each other and space themselves using long calls (8, 10, 13).

Mating System

The orangutan mating system is called short term polygyny. This means individuals can select new mates every year. Both males and females may have multiple mates, although individuals may breed with the same mate over more than one pregnancy . Adult males and females normally mate during consortship often initiated by females (8,14). Forced copulations with females do occur, most often by subadult males (15). However, many offspring are conceived during consortship with adult males, indicating female mate selection may be an important factor in reproductive behavior.

Daytime Activity

Long-term observations of wild orangutans show that more than half their daytime activity is spent feeding. Orangutans spend another 30% of their time traveling to food resources and 15% of their time resting. Only 2% of their time is spent in other activities including mating and other social interactions. (These numbers are averaged from studies by Rodman (16), Knott (17) and Galdikas (8). However, orangutans may travel, rest, and forage in association with other individuals without overt social interaction.

Feeding behavior (8,11,12,18,19), ranging behavior (17,21) and response to disturbance (20,21) appear to be the primary factors that determine orangutan distribution within forest habitat.

The orangutan’s unique natural history and socioecology underlie their limited distribution and endangered status.

References

- Rijksen, H.D. and E. Meijaard. 1999. Our vanishing relative: the status of wild orangutans at the close of the twentieth century. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht.

- Singleton, I., Wich, S., Husson, S., Stephens, S., Utami Atmoko, S., Leighton, M., et al. (2004). Orangutan population and habitat viability assessment: Final report. Apple Valley, MN: IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group.

- McConkey, K., 2005. Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) in: J. Caldecott and L. Miles (eds) World atlas of great apes and their conservation. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- IUCN 2007. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. . Downloaded on 15 June 2008.

- Fischer, A., J . Pollack , O . Thalmann , B . Nickel , S . Pääbo. 2006. Demographic History and Genetic Differentiation in Apes . Current Biology , Volume 16 (11): 1133 – 1138

- Delgado, R.A., C.P. van Schaik. 2000. The behavioral ecology and conservation of the orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus): A tale of two islands. Evolutionary Anthropology 201-217

- Marshall, A.J., R. Lacy, M. Ancrenaz, O. Byers, S. Husson, M. Leighton, E. Meijaard, N. Rosen, I. Singleton, S. Stephens, K. Traylor-Holzer, S. Utami-Atmoko, C.P. van Schaik, S. Wich. Chapter 5: Orangutan population biology, life history, and conservation: perspectives from PVA models. In S.A. Wich, S.S.U. Atmoko, T.M. Setia, C.P. van Schaik (eds). Orangutan ecology, evolution, behavior and conservation. in press.

- Galdikas, B.M.F. 1978. Orangutan adaptation at Tanjung Puting Reserve, Central Borneo. PhD dissertation.

- Galdikas, B. Modern adaptations in orangutans? Nature 291 (5812) 266, 1981.

- MacKinnon, J. 1974. The behavior and ecology of wild orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus). Animal Behavior 22:3-74.

- Galdikas, B.M.F. 1988. Orang utan diet, range and activity at Tanjung Puting, Central Borneo. International Journal of Primatology 9:1-31.

- Wich, S., R. Buij, C. van Schaik. 2004. Determinants of orangutan density in the dryland forests of the Leuser Ecosystem. Primates 45:177-182.

- Galdikas 1983. The orangutan long call and snag crashing at Tanjung Puting Reserve. Primates 24 (3): 371-384

- Fox, E.A. 1998. The function of female mate choice in Sumatran orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus abelii) PhD Dissertation, Duke University.

- Galdikas 1979. Orangutan adaptation at Tanjung Puting Reserve: mating and ecology. PP 194-233 in The Great Apes. D.A. Hamburg and E.R. McCown eds. Benjamin/Cummings Publ. Co., Menlo Park, California, 554 pp.

- Rodman, P.S. 1988. Diversity and consistency in ecology and behavior. In Schwartz J.H. (ed) Orang-utan biology. Oxford University Press p 31-51.

- Knott, C.D. 1999. Orangutan behavior and ecology. In: P. Dolhinow, A. Fuentes (eds) The nonhuman primates. Mountain View: Mayfield Publishing. P 50-57.

- Van Schaik, C.P., A. Priatna, D. Priatna. 1995. Population estimates and habitat preferences of orangutans based on line transects of nests. In: Nadler, R.D., Galdikas, B.F.M., Sheeran, L.K., Rosen N. (eds) The neglected ape. Plenum Press, New York, pp-129-147.

- Buij, R., S.A. Wich, A.H. Lubis, E.H.M. Sterck. 2002. Seasonal movements in the Sumatran orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus abelii) and consequences for conservation. Biological Conservation 107:83-87.

- Felton, A.M., L.M. Engstrom, A. Felton, C.D. Knott. 2003. Orangutan popualtion density, forest structure and fruit availability in hand-logged and unlogged peat swamp forests in West Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biological Conservation 114: 91-101.

- Morrogh-Bernard, H., Husson, S., Page, S.E., Rieley, J.O., 2003. Population status of the Bornean orang-utan (Pongo pygmaeus) in the Sebangau peat swamp forest, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Biological Conservation 110 (2003) pp. 141-152.