In the mid 1970s, two retired Indonesian Army Generals, one of whom had been the very popular Chief of Police for all of Indonesia, gave me their four orangutans. One of the retired Generals, who spoke English quite well because he had been a prisoner in Europe during the Second World War after being captured while fighting for the Dutch, had written me. He had read about my work in Jakarta newspapers and knew that we were rehabilitating wild born ex-captive orangutans. He told me that he had a subadult male orangutan named Gundul and asked if we would rehabilitate Gundul and bring him back to the wild in Borneo. The former Police Chief had four orangutans. I refused to take his Sumatran orangutan back to Borneo but brought his three Bornean orangutans back to Kalimantan along with Gundul. One of the Police Chief’s orangutans was Siswoyo.

When we took the four orangutans back to Borneo, the Indonesian Air Force flew us from Jakarta in a large cargo plane. The Generals’ orangutans going back to the wild in Borneo was big news in Indonesia, which at the time was said to be a “military dictatorship.” Rod and I were featured not only on the front pages of newspapers in Jakarta, but also on Indonesian television. It was a piece of good news for everybody. Everybody applauded the two Generals who were voluntarily returning their orangutan pets back to their habitat.

Siswoyo was named after Mrs. Siswoyo whose husband, a Forestry official, had been very helpful to us. Confined for six years in a tiny metal cage in the middle of a busy open courtyard in the center of the Police Chief’s house, orangutan Siswoyo was semi-paralyzed when she arrived at Camp Leakey. She could only slowly squat-walk because she could not raise herself above her haunches nor could she open her hands. Shortly after her arrival, Siswoyo refused to eat. She was obviously traumatized. After all, one day she was in a tiny cage in the middle of one of the largest cities in the world and the next day she was in the middle of the jungle. I nursed her for a long time and paid much attention to her. She started going out into the forest and eventually, over time, regained the use of her limbs to the point where she could walk on all fours. She also regained the ability to open and close her fingers on both hands. I finally persuaded her to start eating after much effort by providing her with our precious spaghetti pasta and tomato sauce which we had persuaded our Pangkalan Bun merchant to import from Java. By 1976, she was going into the forest much more, although she had to be “rescued” several times when she didn’t return to Camp. Once we found her some distance from Camp sitting in a swamp puddle looking dazed and befuddled.

Once Siswoyo started eating, she packed on the pounds. One day, a wild adult male walked into Camp Leakey. It was clear he was interested in Siswoyo. He long called. Siswoyo seemed ambivalent about his presence. She seemed attracted to him but also frightened. Sometimes in his presence, Siswoyo would start running and jump on my back. I didn’t know what to do so I ran with this heavy orangutan while being chased by a large wild adult male on the ground. It was nerve-wracking. But his interest was Siswoyo, not me. He was around for a short while and then approximately eight and a half months later in 1977, Siswoyo gave birth to a three-pound infant. Unfortunately, the infant soon died. But Siswoyo consorted with wild males again and in September 1978 she gave birth to a female infant whom we named Siswi. By this time, Siswoyo was a lumbering tank. She was the largest wild born ex-captive female orangutan that ever lived at Camp Leakey. She wasn’t fast, but she was big. After giving birth to Siswi, she soon became the dominant female orangutan in Camp Leakey. I don’t remember seeing her in any close interaction with wild orangutan females, but when she moved down the bridge at Camp Leakey where the feeding station was initially located, it was like Moses parting the Red Sea. All the other orangutans, including young males, would jump off the bridge or move out of her way as she progressed towards the end of the bridge. Interestingly, she never had a confrontation with Akmad, who was the dominant female in Camp Leakey until Siswoyo’s arrival. Siswoyo never challenged Akmad and Akmad never challenged her. It was as if they had a pact to be co-dominant in parallel. Akmad’s dominance differed from Siswoyo’s in that Akmad sometimes threatened and very occasionally nipped other adult females, but it was her serene presence and confidence that enforced her dominance. Akmad was a born aristocrat with no need to flaunt her status. Siswoyo, on the other hand, enforced her dominance with threats that occasionally were followed by harsh aggression. While female orangutans moved out of Akmad’s way respectfully and gracefully, they jumped out of Siswoyo’s way when she came barreling down the path. But ironically, Siswoyo was sometimes sweet and gentle, especially to young male orphans. One of these, when he grew older, became a dominant male. I often thought that Kusasi learned the expectation of dominance from the reactions of the other orangutans who jumped out of his adopted mother’s way as he trailed behind Siswoyo when she moved towards the feeding station.

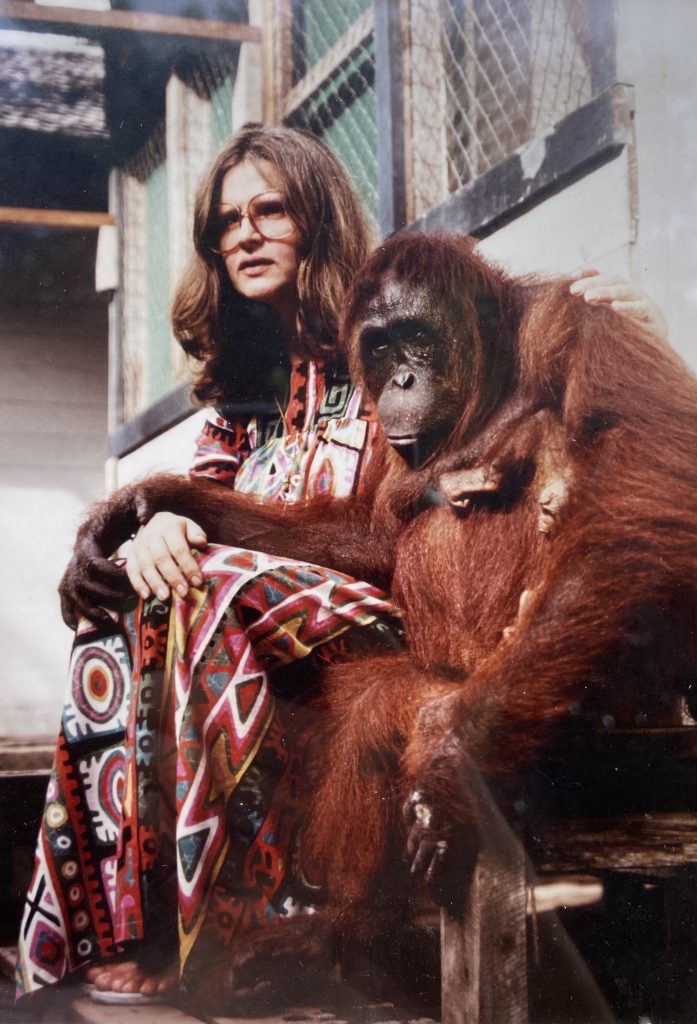

Siswoyo and I became best friends, and part of it had to do with the fact that in the very early days of her presence at Camp Leakey, I took care of her, nursed her, fed her when she refused to eat, and searched for her when she didn’t come back from the forest. She would jump on my back and expect me to carry her, with infant Siswi clinging to her, even when Siswoyo became a very large adult female. A few times she surprised me when I was searching for wild orangutans by creeping up to me and jumping on my back. The first time it happened, I was so startled I almost fainted. I had no idea what or who it was that had hoisted themselves on my back, especially since she had a habit of flinging her arm across my throat and almost strangling me. I couldn’t breathe. After this happened a few times, I realized that it was Siswoyo who had seen me walking in the forest and wanted a ride back to Camp Leakey.

Through the years, Siswoyo gave birth to Simon (named after Simon Fraser University where I teach one semester per year) and Sugarjito (named after one of my first students who received his PhD and became an important Indonesian conservationist).

After Siswoyo became a mother and spent much time in the forest, she would often come back to Camp in the late afternoon. If I was inside my house, she would give an awkward knock and wait for me to come out. The two of us would lazily sit there on my front porch, looking out into the canopy of the trees surrounding my house and listening to the sounds of the forest. Siswi, as she grew older, became braver and would leave Siswoyo and play nearby. Siswi was occasionally jealous when I came too close to Siswoyo, but that attitude eventually disappeared. Siswoyo did not ask for food. She sometimes took the cup of tea or coffee that I was drinking but our friendship was best exemplified by the two of us sitting silently next to each other on the wooden floor of my porch. She sometimes would hold my hand or throw an arm over my arm or on my lap. Our friendship had nothing to do with food. We simply liked each other’s company. She could relax with me because there was no dominance. We were coequal, two mothers of two species at peace in each other’s presence. If she wanted my tea, I gave it to her. She wasn’t particularly interested in breaking into my house. We just sat there, two good friends. Sometimes if my children were there at Camp Leakey, which they often were, they would come out and play with Siswi and even affectionately pounce on Siswoyo. Those times in the 1980s when Siswoyo and I sat next to each other on my porch constitute some of the best memories of my entire life. At that time, there were virtually no people at Camp Leakey. The relatively few staff members spent most of their time, like I did, in the forest, and there was only the very occasional local visitor. As with Siswoyo, the staff would return from following wild orangutans in the late afternoon or early evening. The main presence at Camp Leakey were the orangutans. Camp Leakey seemed like a piece of eternal paradise. A virtual garden of Eden.

I was very fortunate to have Siswoyo as my friend. But unfortunately, she died after childbirth in the early 1990s. I was away because of an orangutan emergency that had developed in Jakarta. A Canadian colleague with whom I was conducting research had remained at Camp Leakey after my departure. She tried to save Siswoyo by giving her oral antibiotics. It wasn’t enough. It didn’t help. Siswoyo died at Camp Leakey. I also remember my departure from Camp Leakey at that time. I was on the bridge at Camp Leakey walking towards the dock. While the boat waited for me, Siswoyo came up to me and did something she had not done before. She threw her arms around my legs and hugged me so fiercely that I couldn’t move. She would not let go. I eventually wriggled free and was able to walk to the boat. That was the last time I saw Siswoyo alive. After her death, I vowed that we would build a veterinary hospital for orangutans and other wildlife so that we could treat them and save them. But there were many crises, emergencies, and priorities in the 1990s that took precedence. So my dream was accomplished, but it took a lot longer than I thought when I returned to Kalimantan after Siswoyo’s death. The Orangutan Care Center and Quarantine, that was built in the 1990s, remains a tribute to Siswoyo.